Commentary by Kirsten WILLIAMS

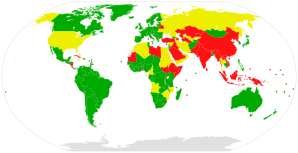

– Green: State party.

– Blue: State party for which it has not entered into force.

– Yellow: Signatory that has not ratified.

– Red: Non-state party, non-signatory.

The African Union (AU) met for its 26th summit last week, with the official purpose of discussing the human rights, reform and trade issues facing the continent. However, much of the media coverage surrounding the summit concerned the AU’s relationship with the International Criminal Court (ICC). At the convention, the AU voted to draw up a roadmap towards a potential withdrawal from the court. Although the AU cannot withdraw as a block, it will encourage individual member states to do so. The ICC is thus faced with the biggest challenge to its existence that it has ever known.

Since every investigation launched by the ICC was in Africa before the recent decision to investigate the Georgian war, the court is often accused of being biaised against Africa. Some African leaders have lambasted the court as a tool of racism and Western imperialism. In 2013, members of the African Union agreed to counter the ICC’s reach by appealing to the UN Security Council and encouraging AU members to withdraw from the treaty establishing the Court. The ICC has therefore long been involved in a battle with the AU for authority on the continent, and by all accounts it is losing.

Indeed, though African countries have consistently threatened to pull out of the ICC’s jurisdiction, the calls for a mass walkout have intensified recently. The latest campaign is spearheaded by the Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta, who wants his African counterparts to leave the court in protest against the ongoing trial of former Kenyan vice-President William Samoei Ruto and broadcaster Joshua Arap Sang.

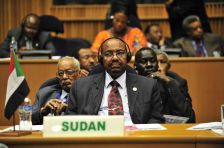

Even staunch supporters of the ICC, like South Africa, are considering the Kenyan president’s proposal. Relations between Cape Town and the ICC became fraught over the decision to allow Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, to fly back home following an African Union summit in South Africa despite an ICC warrant for his arrest. The ICC furiously criticised the decision, and South Africa retaliated by “reconsidering” its membership of the court.

The withdrawal of the AU would be disastrous for a court already struggling with a number of controversies. Only last week, in a hearing at the prosecution of former Ivory Coast president Laurent Gbagbo, the names of anonymous witnesses were accidentally broadcast to the court, which was in turn being filmed. The ICC lacks the credibility it desperately needs to refute allegations of racial bias. It is also fast running out of resources. With austerity continuing to bite worldwide, government contributions to The Hague have been significantly reduced, leaving the court struggling to cope with its workload.

On the other hand, the court is showing signs of evolution. After half a decade of preliminary examinations, the ICC has made the historic step of deciding to bring belligerents of the South Ossetian war to trial. The war, in 2008, was fought between Russia, Georgia, and Russian-backed separatists in the South Ossetia region. The ICC’s decision to investigate perpetrators of violence has been lauded by international human rights groups and comes at a time of increased anti-Russian sentiment, which will bolster praise for the court.

Nonetheless, major countries remain outside the jurisdiction of the court, like the US, Egypt, Israel and Russia. That means that the court will likely continue to be accused of anti-African sentiment despite taking on the Georgian case. The next years will be crucial for ensuring African support for the court. If the AU continues to counter the court’s warrants and warnings, the court could fail, leaving the world without an institution for global criminal prosecutions.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Great Post

LikeLike

Thanks! We really appreciate it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

welcome

LikeLike

It is self preservation on the part of the African political elite that is the primary driver of the ‘Anti-Africa’ and Imperialism accusations leveled against the court. Having hobbled the law and order mechanisms in their own home countries, these leaders seek to avoid accountability wherever the prospect of genuinelly being held to account for their misdeeds may occur.

LikeLike